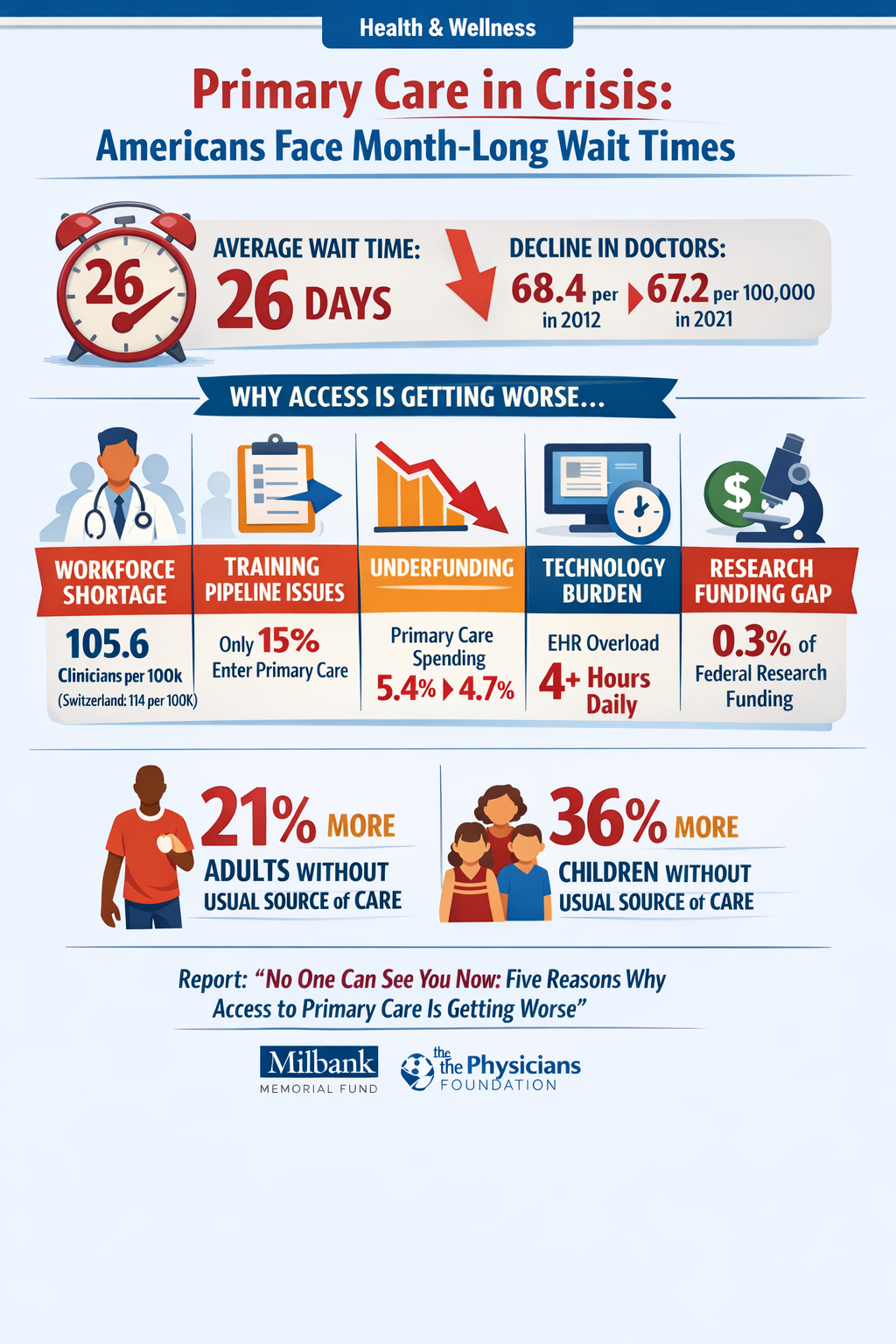

Primary Care in Crisis: Americans Face Month-Long Wait Times

A comprehensive 2024 scorecard report reveals a deepening crisis in U.S. primary care access, with average wait times reaching 26 days and the number of primary care physicians per capita declining from 68.4 per 100,000 people in 2012 to 67.2 in 2021.

The report, "No One Can See You Now: Five Reasons Why Access to Primary Care Is Getting Worse," published by the Milbank Memorial Fund and The Physicians Foundation, identifies five critical factors undermining primary care:

-

Workforce shortage: Despite growth in nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), total primary care clinician density remains insufficient at 105.6 per 100,000—well below comparable nations like Switzerland (114 per 100,000 physicians alone).

-

Training pipeline failure: Only 15% of physicians actually enter primary care practice within 3-5 years after residency, despite 37% initially training in primary care specialties. Over half subspecialize or become hospitalists instead.

-

Chronic underinvestment: Primary care spending dropped from 5.4% of total healthcare expenditures in 2012 to 4.7% in 2021, with declines across Medicare, Medicaid, and commercial insurers.

-

Technology burden: Nearly half of family physicians rate their electronic health record (EHR) usability as "poor" or "fair," with over 25% reporting overall dissatisfaction. Many physicians spend 4+ hours daily on EHR tasks outside patient care.

-

Research funding gap: Only 0.3% of federal research funding goes to primary care research, limiting innovation in care delivery and payment models.

The consequences are stark: Between 2012 and 2021, the percentage of adults without a usual source of care increased 21%, while children without a usual source of care rose 36%. This erosion of access particularly accelerated after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Read the full scorecard report

Commentary

This report provides crucial data backing what many Americans experience firsthand: getting an appointment with a primary care doctor has become increasingly difficult. Several interconnected factors deserve closer examination:

The Economics Don't Work: Primary care physicians earn significantly less than specialists while facing similar educational debt burdens. When combined with higher burnout rates and unsustainable workloads, it's no surprise that medical residents increasingly choose specialization. The 5% spending on primary care—which provides the foundation for the entire health system—represents a fundamental misallocation of resources.

Community Health Centers as a Bright Spot: The report notes that areas with higher social deprivation actually have more primary care clinicians per capita (111.7 per 100,000 vs 99.5 in less disadvantaged areas). This unexpected finding likely reflects the success of federally qualified health centers, which now serve 1 in 11 Americans. However, these centers operate on thin margins with unstable Congressional funding, unlike the $16 billion Medicare automatically provides to hospital-based residency programs.

The Hidden Training Crisis: The statistic that only 15% of training physicians enter outpatient primary care (versus the commonly cited 21% who enter "primary care" including hospitalists) reveals how workforce projections have been systematically overstated. Meanwhile, just 4.6% of primary care residents train in underserved community settings where they're most needed.

Technology as Burden, Not Solution: The EHR dissatisfaction data illuminates why primary care panel sizes are shrinking despite technological "efficiency" gains. When technology adds 4+ hours of daily administrative work rather than streamlining care, it actively reduces access. This suggests current health IT certification standards prioritize billing and compliance over usability.

International Comparison: The U.S. primary care physician density of 67.2 per 100,000—or even 105.6 including NPs and PAs—compares poorly to peer nations. Canada has 133 primary care physicians per 100,000. This isn't just about absolute numbers; it reflects different health system priorities and payment structures.

The Fragmentation Problem: The report notes the emergence of "two distinct arms" of primary care: traditional relationship-based care versus episodic care through telehealth-only services, retail clinics, and urgent care. This fragmentation may appear to increase access but likely increases costs and reduces quality through lack of care coordination.

Policy Solutions Exist But Lack Implementation: The 2021 NASEM report "Implementing High-Quality Primary Care" provided 16 detailed policy recommendations. Three years later, implementation remains minimal. Some states have begun tracking or mandating primary care spending increases, and CMS has introduced new payment models, but these efforts don't match the scale of the crisis.

The data gaps identified in the report—particularly around NP/PA training pathways, wait times, team composition, and Medicare Advantage payment practices—represent another obstacle to reform. Without comprehensive data, policymakers lack the information needed to design effective interventions.

For individuals seeking care now, the report's title captures the frustration: "No One Can See You Now." The solutions require systemic change in how we fund medical education, pay for primary care, design health IT, and structure the healthcare workforce—changes that will take years to implement even with political will. In the meantime, Americans' health outcomes will continue to lag behind other developed nations, with the gaps largest for those in underserved communities.